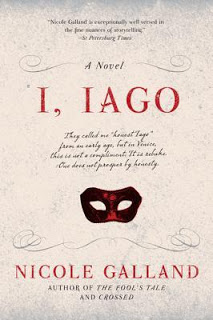

I, Iago skillfully retells Shakespeare’s Othello as the Tragedy of Iago, following the famous villain through the course of his career and explaining just how he came to be the mastermind orchestrating the downfall of a proud general and all those connected to him. In doing so, Galland fills in some of the gaps of Shakespeare’s narrative, showing us how Iago came to be who he is and chronicling the circumstances that change him from a loyal friend and subordinate to a scheming, vindictive meddler.

The book divides into “Before” and “After,” meaning before and after the point where the play Othello begins, and each half is quite interesting in its own way. In “Before,” we get the development of Iago as a person. Galland’s research serves her well here — early modern Venice springs to life in vivid detail, particularly with regards to its military and political matters. We meet Iago as a young man, and he explains that he has always been known as “honest Iago” — not a compliment in Venice, where the ability to quibble, to flatter, and to evade has far more value than blunt truth. Iago lacks subtlety, always speaking his mind, and taking decisive action rather than weighing the consequences beforehand. He is boyhood friends with Roderigo, though he disdain’s the other boy’s weakness and lack of gumption; they grow apart as they grow older, with Roderigo following his family’s mercantile endeavors. Though Iago has scholarly leanings, his family’s prerogative forces him into the military, where he excels, first in the artillery, then in the army. Along the way, he woos and wins Emilia, the only woman he’s ever met with whom he can tolerate much conversation, and their marriage is a blissfully happy one. When Iago meets Othello, there is instant camaraderie; they meet at a masked ball during Carnival, and the circumstances echo their characters. Neither man can hide what he is, though Othello more obviously, thanks to his skin tone. Iago, on the other hand, suffers that inability in his character. Throughout the book, we see him incapable of wearing a mask, both literally and figuratively — in every Carnival scene, he ends up discarding his vizor, and his ungoverned tongue and open expression display his blunt opinions at every turn. The two men sense a commonality between them, a lack of patience with the artifice and genteel dishonesty of Venice. Iago comes to think so highly of Othello that there’s nothing he wouldn’t do for him, including helping to conceal his epileptic fits from the Venetian Senate. He follows Othello to war, to disastrous ruin on Rhodes, and to the altogether different battleground of patrician dinner tables and courtly galas. There, in the household of Brabantio, Othello meets his undoing: a girl named Desdemona, enraptured with the idea of him. Iago counsels him against the courtship, explaining that no Venetian patrician would ever let his daughter marry outside of that narrow caste; Othello pretends to give up the infatuation, but in fact corresponds with Desdemona in secret and eventually planning an elopement — and since Othello has little more talent for deceit than Iago, Iago has little trouble uncovering the scheme.

In the “After” section, we watch this character, whom Galland has rendered quite likeable, fall. Othello betrays Iago’s trust, giving a coveted lieutenancy to the less-qualified Michele Cassio as a reward for assisting in his covert courtship of Desdemona. Emilia is, to Iago’s eyes, inexplicably supportive of the deceitful romance, and therefore complicit. Feeling wounded and discarded by those he most loved and trusted, Iago’s bitter hurt prompts his plans for revenge.

I call this book the Tragedy of Iago because it tracks his rise and at least partially self-constructed fall in a way that renders him both likeable and pitiable. Galland makes a wise choice, spending the first half of the book on events we never see in the play, because it gives the character a more solid background, particularly in regard to his relationship with Othello. In Shakespeare’s play, the audience hears of their association and implied friendship, but we never truly get to see it; we know from the start that Iago is working to ill ends, because he tells the audience so in barest terms. In I, Iago, the friendship is palpable, heart-warming — and so Othello’s betrayal of Iago has a real emotional effect. When Othello begins to shut Iago out in favor of Cassio, the reader is privilege to Iago’s pain and bewilderment. We also get new motivation for Iago’s actions — jealousy and revenge play their parts, and no mistake, and Iago freely admits that he wants to hurt his friend for hurting him, to disgrace the usurper Cassio, and to remove Desdemona from the picture (though he does not intend to do so through her death). That isn’t the total of what’s going on in Iago’s head, however; when he sees how easily Othello can be roused to dangerous passions, he starts to harbour deep concerns about the general’s ability to serve in the position of honour and responsibility with which the Venetian Senate has placed him. He worries, too, about Othello’s judgment; a man who will pass over more qualified men in order to hand positions to panderers, after all, demonstrates an ethical lapse. Iago never claims to be operating only for the common good, in removing a potentially dangerous commander from his post — but since that lines up neatly with his desire for revenge, why not work for both?

The dual nature of the tragedy is most obvious in the moment when things spin past Iago’s ability to control them. His words have an effect far greater than he expected, as Othello proves so easily inflamed where his wife is concerned. The subtler tragedy is that turning Iago from honesty to deceit. He has to learn that trait, a talent foreign to him from birth, and it’s terrible to see him do so — to see a good man corrupted by an unfair world. Iago becomes almost drunk on it, overindulging, swept up by his newfound power, pushing limits to see how far he can take his lies before they become too improbable — and astonished when that barrier never seems to impede him. He learns deceit from those who deceived him, and since we have the juxtaposition of his stalwart honesty in the “Before” section, the transformation is all the more calamitous.

The book is best when it’s not trying to out-clever itself. The moments where I grimaced were when Galland was cramming in bits from other Shakespeare plays that didn’t quite belong — having Iago banter with whores and his military comrades by using lines from Measure for Measure and As You Like It, much of his courtship with Emilia coming straight out of Much Ado about Nothing– because they were jarring, discordant. The tenor was so different from the story she’d been telling that it seemed an odd digression. Initially, this made me nervous for the second half of the book, which covers the plot of Othello, but Galland actually handled the dialogue there quite smoothly. We hit the major points and get the biggest quotes without much interference, but most of the conversations are taken out of verse and into more natural prose in a way that doesn’t seem forced or awkward. The story does rather hurtle itself through the climax and denouement, however, and while that is perhaps appropriate, given how circumstances spiral out of Iago’s control, I could have done with a little more fulfillment, since we had so much build-up to the cruc

ial moments.

This book leaves me wanting the story from yet more angles — Emilia’s, for instance. We only ever see her through Iago’s eyes, and though it’s clear she’s an intelligent and independent woman, she remains only an object throughout this novel. Because everything is first-person narrative, we lose her in the moments when Iago’s not there — which are some of her finest moments in the play. We never really get to know what she’s thinking, and as Iago begins on his plot of vengeance, he distances himself from her, both because he wants to protect her and because he no longer quite trusts her — which has the effect of removing her from the reader as well as from himself. This book is definitely the story of men; Emilia and Desdemona are intriguing, but peripheral, and since Iago never understands either of them, the reader doesn’t get that opportunity, either.

Overall, I, Iago is an entertaining and thoughtful adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello. The prose is well-constructed, the historical research thorough, and the characters well-drawn. Galland explores the story from an intriguing angle and creates a more three-dimensional world, situating Venice and its characters in the larger world. Whereas Shakespeare narrows in, focusing his scope tighter and tighter until it fits in a single bedroom, Galland allows us to see how this tragedy ripples outward. I think most Shakespeare enthusiasts will find a lot to like about this book, and if there are also some points to criticize — well, most of us enjoy that, too.

Excellent review. Just got done w/the book, myself, today. Definitely agree on the cramming of other Shakespeare plays, it definitely was a bit much … I had to laugh out loud w/"Who would have thought a lily livered merchant to have so much blood in him?" Other than that? I fantastic-quick read.