The thing about being active in social media, in fandoms, on the Internet in general is that it exposes you to a broader spectrum of humanity than most people encounter on a day-to-day basis — and it means that a lot of minority groups get greater exposure on the Internet than they do elsewhere. A lifelong citizen of the web, I’m always learning new things from new groups of people. Because I’m politically interested and active, a lot of the things I learn have to do with civil rights, and because of the nature of current politics, a lot of those rights have to do with sexual attraction and gender equality, in some way or another. I’ve noticed a trend, in the past few years, of increasing awareness of people who do not conform to the socially projected binary system: people who are neither male nor female, but somewhere in between; people who are not cisgendered, whose mental, emotional, psychological identities don’t match with their biological organs; people who are neither heterosexual nor homosexual, but bi-, or pan-, or asexual, or who are still figuring that out. It’s a big wide world out there, and there are all kinds of people in it — but just because we didn’t hear as much about these people before doesn’t mean they suddenly started existing in the past few years. These ideas have been around for centuries, even millennia — and Shakespeare had something to say about them, albeit in a different language than we use today.

Five years ago, I don’t know that it would ever have occurred to me to use the terms “gender fluidity” or “sliding scale of human sexuality” (and I hadn’t even heard the term “cisgendered,” which is still new enough that it has yet to make it into the OED) — particularly not in a Study Guide aimed for teachers of high school and college students. And yet, in an activity I’ve been preparing for the Twelfth Night Study Guide, I’ve done just that. Viola gives me a great in — and so does Antonio, and so does Olivia, so do Orsino and Sebastian. In “Perspectives: Gender and Behavior,” I ask teachers to lead their students through an exploration of the gender dynamics in the play. The activities involve looking at the stereotypical presentations of male and female, both in appearance and behavior, examining how Shakespeare invokes these markers in the plays with cross-dressing heroines, and then exploring how the gender confusion creates emotional conflict . As with all our Study Guides, the main focus of the activity is practical — how do we stage this? How do costumes affect the presentation? How can an actor play against his or her biological gender or usual presentation of gender? But, as this is the Perspectives section, I also take a moment to broaden the scope — to explore the social issues the play raises, particularly in modern performance, and how those issues may resonate in students’ lives. And so part of the activity looks like this:

- Give your students Handout #5A: Suit Me Like a Man. This handout provides the text of the scenes from five Shakespeare plays where the heroine makes the decision to dress as a man:

- Discuss:

- What do Shakespeare’s cross-dressing heroines point to as the markers of masculinity versus femininity?

- What information does Shakespeare convey about how his (male) actors playing female characters will present masculinity?

- All of these heroines have help in assuming their disguises. Julia and Portia ask their waiting-women; Rosalind has Celia for a comrade; Viola asks the sea captain; Imogen takes the suggestion from Pisanio. How do these relationships pertain to the social anxiety surrounding cross-dressing? Is it different for Viola, who asks a man for help? For Imogen, the only one among the five who does not have the idea herself, and cross-dresses at a man’s suggestion?

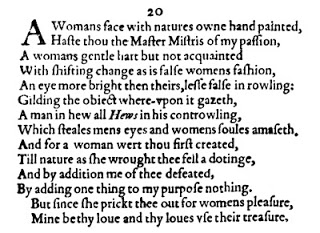

- Further Exploration: Look at Shakespeare’s sonnets for more commentary on the comparison and confusion of gender (particularly Sonnet #20). What continuing relevance do these poems and the gender-bending heroines in the plays have in the modern world, as we begin to consider more frequently ideas of gender identity, gender fluidity, and the sliding scale of human sexuality? How is the social anxiety expressed in the plays and poems like or unlike modern social anxiety around the same topics?

It would be easy to write about Twelfth Night without directly addressing these issues — to keep it locked safely in a very narrow interpretation of historical context, to ignore the potential homoerotic implications, to pass over what attention the play can draw to the fluidity of gender assignation and the possible impermeability of identity. I could skip over that. I could avoid what is still, in this country and across the world, a highly controversial topic.

But I don’t want to do that. Because I don’t know who’s in the classrooms that will be using these materials. I don’t know if there will be a girl studying Twelfth Night who has just figured out that she likes girls, or a boy who’s discovering that he likes boys, or boys and girls, or neither. I don’t know if there might be a student of either gender who has never felt right in his or her body, has never identified with what biology provided. I don’t know if there’s someone who, like Viola for much of the play, feels stuck somewhere in the middle. I don’t know who they are. I don’t know if they get support at home or from their friends, or if they’re dealing with it all in silence and isolation. I don’t know how often they hear that they’re sinful, or sick, or monstrous. And so I don’t want to close doors for them. I want to give teachers the tools explore these ideas where they live in Shakespeare’s works, rather than skimming past them.

But I don’t want to do that. Because I don’t know who’s in the classrooms that will be using these materials. I don’t know if there will be a girl studying Twelfth Night who has just figured out that she likes girls, or a boy who’s discovering that he likes boys, or boys and girls, or neither. I don’t know if there might be a student of either gender who has never felt right in his or her body, has never identified with what biology provided. I don’t know if there’s someone who, like Viola for much of the play, feels stuck somewhere in the middle. I don’t know who they are. I don’t know if they get support at home or from their friends, or if they’re dealing with it all in silence and isolation. I don’t know how often they hear that they’re sinful, or sick, or monstrous. And so I don’t want to close doors for them. I want to give teachers the tools explore these ideas where they live in Shakespeare’s works, rather than skimming past them.

Being a teenager is hard enough. Being a teenager who feels profoundly different from his or her peers is even harder — particularly when that difference, in so much of our country, can make you a target for prejudice, ridicule, and abuse. I like the idea that Shakespeare might be able to help, in some small way — to let those teenagers know that, even four hundred years ago, someone was questioning the stability of gender identity. More than one someone, really — Kit Marlowe’s homoerotic themes are hardly subtextual, women writers were challenging society’s gendered expectations of them, and Italian artists frequently explored androgyny and blurred gender lines in paintings and sculptures. The topic was out there in the early modern world, and students should get to know that. Even that long ago, in a world we often perceive as so much more rigid than ours, some people were pushing the boundaries of what it meant to be a boy or a girl, and some were interrogating the nature of sexual attraction. Real people, not so unlike the modern readers, were exploring alternatives to the prescribed norm, questioning their own emotions and desires, and expressing that through art. So this is why I include the discussion topic in the Twelfth Night Study Guide. If Shakespeare can reach across the centuries and help just one student struggling with these issues of identity, then that makes it worth raising the issue.

Hey I just got through with the pages, I should say Pretty nice work done there.Thanks for sharing your ideas!!I really Keep sharing your views appreciate it!English Tutor