Editor’s Note: The following is excerpted from the ASC Education Study Guide on Twelfth Night, available for purchase in our Gift Shop or through lulu.com as a PDF download or a print-on-demand hard copy. You’ve got til November 27th to see our current production of Twelfth Night and discover for yourself how ASC actors portray the confusions and complexities of gender and identity in the play.

Perspectives

Gender and Behavior

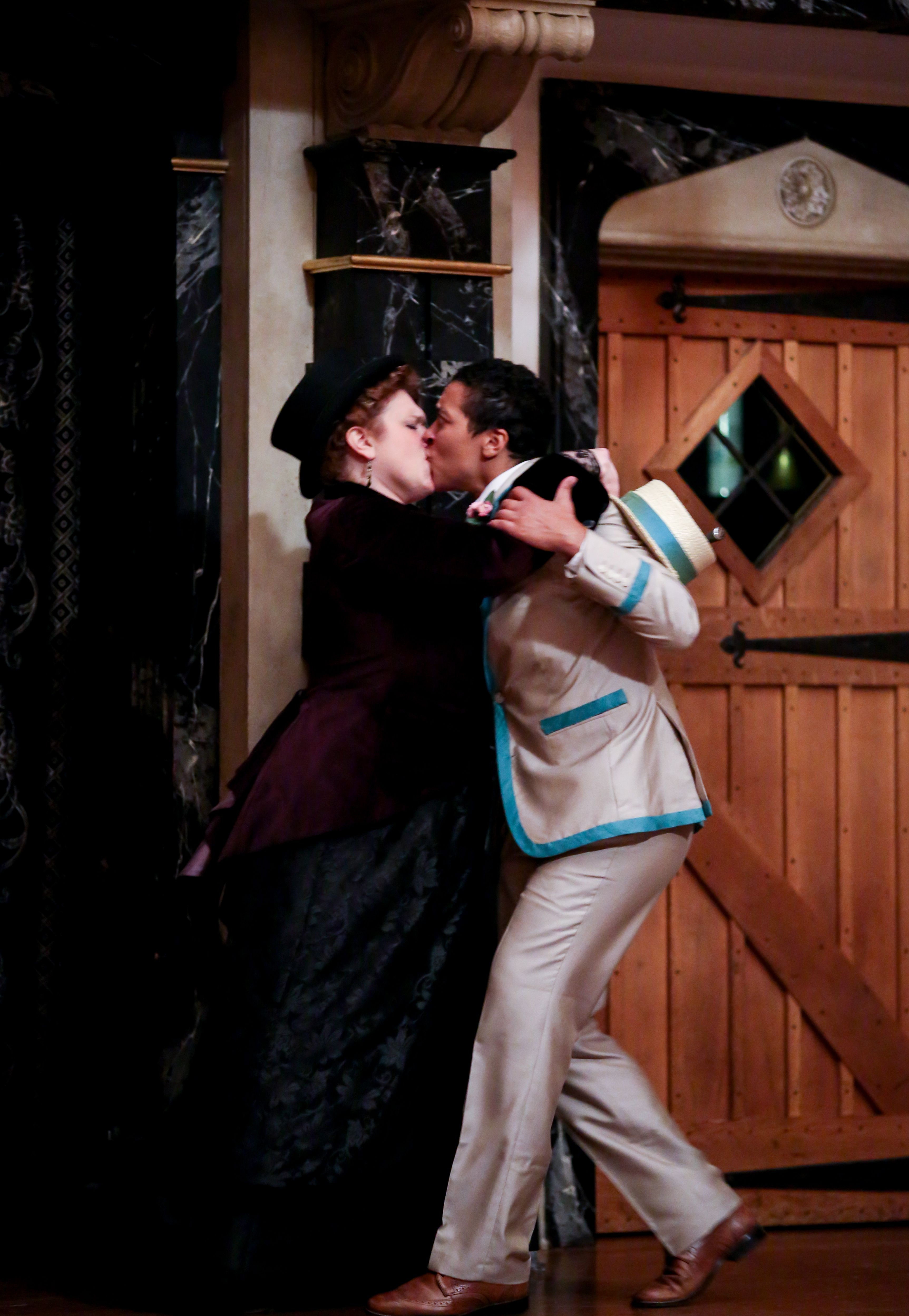

Twelfth Night is one of several of Shakespeare’s plays to feature a heroine who dresses as a man. At the beginning of his career, Shakespeare included a cross-dressing heroine in The Two Gentlemen of Verona: Julia dresses as a pageboy to follow her boyfriend to another city. She reveals herself at the end to stop him from marrying another woman. Julia’s disguise is a plot convenience, allowing her to travel and to observe Proteus without suspicion. Later plays push that plot device further, creating the cross-dressed woman as an object of desire. In As You Like It, written two or three years before Twelfth Night, Rosalind dresses as a boy named Ganymede to travel into the forest; when she runs into her crush, Orlando, she offers, as Ganymede, to pretend to be Rosalind so that Orlando can practice wooing. She also finds herself the object of desire of a shepherdess named Phebe. In Twelfth Night, Shakespeare presses the mismatched desire even further, having a primary character, Olivia, and making that desire a central point of conflict in the play, rather than a side joke. This creates a double-play of suggested homoeroticism; Olivia is in love with Cesario, who is actually another woman, while Orsino thinks he’s falling for a boy, who is actually a woman, who was originally played by a male actor.

Gender issues could prompt quite a bit of social anxiety in early modern England. Many of the anti-theatrical polemics leveled at the playing companies lamented the presentation of boys as women, particularly in romantic roles. Conversely, the idea of women usurping men’s roles suggested an upending of convention. Though a female monarch had ruled England for over forty years – and for all of Shakespeare’s lifetime – women were still considered subordinate to men, legally, socially, and religiously; even Queen Elizabeth spent much of her life pressured by her councilors to find a man to share her throne. Many pamphlets published in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries sought to instruct women on their “proper” place – suggesting that a great many of them had stepped outside the proscribed bounds and entered spheres typically dominated by males. Only two or three years before Twelfth Night, in As You Like It, Shakespeare has Rosalind reappear in women’s garb at the end of the play, which some scholars have suggested was a deliberate method of allaying social anxiety about her ability to resume her feminine role. Viola in Twelfth Night, like Julia in the earlier Two Gentlemen of Verona, never reappears in her “women’s weeds,” remaining in a state of gender ambiguity through the end of the play.

Today, the definition of gender roles remains a hot-button issue. Political debates continue to challenge ideas about balance between the sexes, both socially and financially. In many ways, however, the conversation has changed from determining what one gender or the other can or can’t do to debating the very meaning of gender itself. As the 21st-century begins, advocates for gay, lesbian, and transgender rights continue to push at the boundaries of the binary gender system. In 2010, a British expatriate living in Australia became the world’s officially and legally neuter person, though some cultures of the Indian subcontinent and of Southeast Asia have long recognized the existence of a “third gender.” More recently, transgender advocates such as Laverne Cox, of Orange is the New Black fame, have raised the profile of the transgender population – which has, in turn, led to political debates over bathroom use and legally protected classes. The ongoing gender debate suggests the existence of gray areas between male and female and in the spectrum of sexual attraction – the very sort of grey area that Viola-as-Cesario inhabits.

Twelfth Night, along with the other gender-bending comedies featuring cross-dressing heroines, suggests that, in the view of society, at least, a person’s role in life is more defined by what they wear and how they behave than it is by anatomy. How does Viola challenge or affirm the idea of strictly defined roles for genders? How convincing is her disguise? Several characters tell her during the course of the play that she behaves in a way unbefitting a man, particularly when she does such stereotypically feminine things as fainting at the sight of blood. How does Viola give herself away? How much double-speak does she engage in, allowing the audience to appreciate her duality without explicitly telling other characters about it?

To explore these issues in your classroom, download these sample activities or purchase the ASC Study Guide for Twelfth Night today!