This story started innocently enough. One of my current projects is to complete a full metrical and rhetorical analysis of Romeo and Juliet (as I did for Julius Caesar last year), but in order to begin that, I first have to complete a full check against the Folio. At ASC Education, we like to return to the 1623 First Folio to recover stage directions, emotionally inflected punctuation, and other textual variants which editors have sometimes obfuscated over the years. This practice can lead to a lot of intriguing discoveries; little did I know that one such curiosity yesterday would end up devouring a significant portion of my morning.

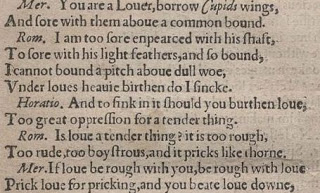

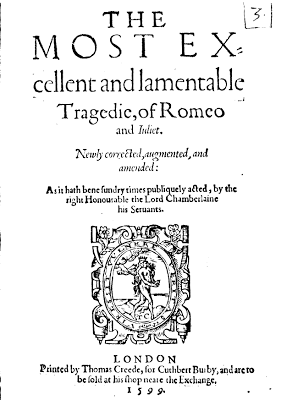

While checking 1.4, where Mercutio and Benvolio attempted to cheer Romeo up as they head for the Capulets’ ball, I ran across the fascinating error at right: Hora. as a prefix, presumably for Horatio. There is no character in Romeo and Juliet named Horatio, though the stage direction for this scene does specify the presence of “five or six other Maskers, Torch-bearers.” ‘How odd,’ I thought. ‘I wonder if that error is in the Q2.’ The 1599 second quarto of Romeo and Juliet is the other reliable text for this play; most modern editions conflate elements from the Q2 and the Folio to arrive at their preferred version of the text (though many slip in elements from Q1 as well). As you can see below, yes, the 1599 Q2 does contain this error — even more explicitly as Horatio. The Folio, then, simply retains what Q2 shows.

While checking 1.4, where Mercutio and Benvolio attempted to cheer Romeo up as they head for the Capulets’ ball, I ran across the fascinating error at right: Hora. as a prefix, presumably for Horatio. There is no character in Romeo and Juliet named Horatio, though the stage direction for this scene does specify the presence of “five or six other Maskers, Torch-bearers.” ‘How odd,’ I thought. ‘I wonder if that error is in the Q2.’ The 1599 second quarto of Romeo and Juliet is the other reliable text for this play; most modern editions conflate elements from the Q2 and the Folio to arrive at their preferred version of the text (though many slip in elements from Q1 as well). As you can see below, yes, the 1599 Q2 does contain this error — even more explicitly as Horatio. The Folio, then, simply retains what Q2 shows.

So I wondered, ‘Huh. How strange. Does this error exist in Q1, then?‘ A quick check revealed that: no, it doesn’t. These lines are not in Q1, which jumps straight from Romeo’s “So stakes me to the ground I cannot stirre” to Mercutio’s “Give me a case to put my visage in,” skipping the pictured section of dialogue entirely. So how did the wandering speech-prefix come about? (And ought I to call it a prefix-errant?).

The simplest explanation is basic printer error: speech prefixes and names were often struck as sets, rather than assembled from individual letters. This practice is why the prefixes and names within the verse generally appear in an italicized font rather than the plain text. It’s easy to imagine, then, that a Horatio, struck for some other play, somehow got mixed in with the Mercutios intended for this scene, and that the type-setter’s quick fingers grabbed it and placed it without the type-setter consciously noticing the incongruity. It’s possible, though I suspect far less likely, that the printer did strike the speech prefix Horatio for this single instance. Perhaps Shakespeare wrote Horatio once where he meant Mercutio (in simple Italianate error, or perhaps thinking of another role the same actor played) and that error stayed in the fair copy or prompt book Creede received to set the type off of. Other similar errors exist, as in the editions of Much Ado about Nothing which have Kemp instead of Dogberry — but each of those gets used more than once. It seems less likely that Creede would create and strike a new full-length nameplate to use only once, so, for the intellectual exercise, I decided to pursue my first theory.

I was at first only tickled by this appearance, amused to picture Hamlet’s best friend getting ready to go to a party in Verona. Did he take a weekend trip away from Wittenburg? Did he decide to move south after the tragedy at Elsinore? Fanfiction-like possibilities abound. But then I remembered — the Romeo and Juliet Q2 was printed in 1599. The first quarto of Hamlet wouldn’t be printed for another four years, so it’s unlikely that the speech prefix was struck for Hamlet‘s Horatio. The light amusement began to grow into a prickling curiosity. What character could it have existed for, then?

The only other Horatio who jumped to my mind is the gentleman in Thomas Kyd’s A Spanish Tragedy — which, as it turns out, had a quarto printed in the same year as the Q2 of Romeo and Juliet in which this error originates. Ah-ha! This seemed to fit my theory perfectly. How easy to make the error if both plays were being printed at the same time, or at least within a reasonably close amount of time — especially since both are full of Spanish/Italianate names.

So, I went to Early English Books Online (EEBO) to find out, first, who printed the Q2 Romeo and Juliet, and if that was the same printhouse that put out the 1599 Q3 of The Spanish Tragedy. Answer: No. Thomas Creede printed the Romeo and Juliet Q2, while William White had the 1599 Spanish Tragedy. The next-earliest Spanish Tragedys were in 1592 and 1594, printed by Edward Allde, so there’s no strong connection there, either.

Who, then, is Horatio? How did this speech prefix sneak in? I felt compelled to push my theory farther. If we accept our Occam’s-Razor-Compatible explanation of a wandering prefix from something else originating at the same printhouse, then what other plays and books were that printer putting out around the same time, and was there a Horatio in any of them? Between 1597 and 1599, Creede printed six other plays, including the 1598 Richard III, John Lyly’s Mother Bombie, and the anonymous Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth, as well as a lot of prose histories. I skimmed through a couple of the plays — no Horatios (though, as a side note, skimming just the stage directions in an unfamiliar play can give you an interesting perspective on it. The Comicall Historie of Alphonsus apparently includes a brazen head, Venus and the Muses, Medea and Iphigenia having a conversation, and at least one murder). I, sadly, do not have the time to look through all of the narrative histories and discourses to see if Horatio appears in the text of any of them. As such, I have no notion where this error originates, who that first Horatio was that ended up reveling with Mercutio and Benvolio, and I may never have that curiosity satisfied. Such is often the travail of academia.

Why does any of this matter? I recognize that, while I found this to be a wonderful scavenger hunt and an entertaining game, not everyone is thoroughly geeky enough to share those effusive emotions about a relatively minor textual variant. So what’s the practical application? Well, that has to do with the choices editors have made in repairing the error over the years. Every modern edition of Romeo and Juliet that we have here in the ASC Education office assigns those lines to Mercutio. It makes sense. He and Romeo are enjoying a back-and-forth. But… they don’t have to be Mercutio’s lines. Would anything change by giving them instead to Benvolio? It would certainly make him more involved in Mercutio and Romeo

‘s conversation, part of their lively sparring, not separate from it. What sort of a different Benvolio might that yield for the entire production? I don’t know, but I’d like to give that option back to production companies and classroom discussions so that we can find out.

thanks for share.