In these socially distant days, many of us are aching for connection. As the live event industry scrambles to stay viable in a word where mass in-person gatherings pose a threat to public health, more and more theatres are embracing digital methods of distributing content by streaming shows through various online platforms. American Shakespeare Center offers several titles through BlkFrsTV, and for non-ASC offerings The Guardian rounds up a few dozen of the theatrical streaming opportunities to be found on the internet this fall, including an on-demand production of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde available from Blackeyed Theatre through December 31, the entire archival holdings of The Globe (and its newer Jacobean counterpart, the Wanamaker) available for rent, and, of course, Hamilton. Whether a recording of a play still counts as, well, a “play” and not a “movie” is a debate for another time — the point is, the necessity of digital distribution is forcing the world’s theatres online.

Technology has allowed modern life to continue in the midst of a global pandemic in ways our ancestors could never have dreamed possible. Applied to a medium built on the power of the collective human experience, this digital shift to solitary and asynchronous viewing has some obvious consequences on the theatrical art form. Theatre is a social experience, and Coronavirus isn’t the only thing catching in a crowd. Emotions are contagious, and feelings of joy or outrage are infectious in the communal environment of the playhouse. Watching a production (even a live one!) at home, alone, separated from the feedback of the other audience members and thus trapped in the solitary silence of your own experience…. it doesn’t quite scratch the itch to connect the way live theatre used to do. What to do?

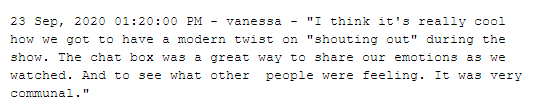

During #SHXCamp 2020, we found that the various chat functions on programs like Zoom could actually be a fun and useful way for socially distant audiences to connect to and with each other synchronously — and without disrupting the meeting, class, show, or presentation at hand. As we began live-streaming evening performances from the 2020 SafeStart season out to the school groups we would normally be visiting on tour, we started using the chat function in Vimeo to recreate online some measure of the (emotionally, not virally) contagious communal experience the students would otherwise have experienced in the Playhouse.

Audiences (whether student or regular) can abuse chat features easily, of course, and teachers and venues alike are often reluctant to deploy them. After all, we don’t normally encourage students to pass notes in class, nor do we generally encourage audience members to chat through a show. (To which I say: why not? Again, a debate for another day.) With some ground rules (and some gentle reminders) we’ve found that most people are happy to play nice and to play along, but still. Does the potential reward of connection outweigh the ever-present risk of somebody being a jerk and ruining it for everybody else?

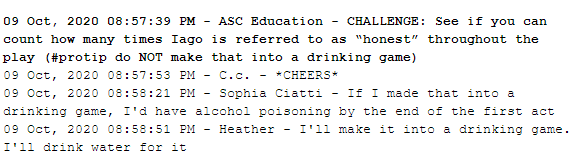

Enter the ASC Education Vimeo Chatbot, as I like to call it. Every time ASC streams a live performance of Othello or Twelfth Night out to an audience via Vimeo, a member of ASC Education hangs out in the chatbox to answer questions, provide textual commentary and production trivia, and facilitate conversation. Those who choose to watch the performance uninterrupted can hide the chat easily, but those who choose to engage with the Chatbot (usually played by Education Associate Aubrey Whitlock or myself) or with the others who are watching are always able to do so. And, like magic, they do!

Sometimes, audiences need some encouragement from the Chatbot persona in order to engage fully with the chat, which is where the occasional prompt, challenge, and fun fact can be really useful. Other times, audiences need nary a nudge to take over the chat themselves. On those nights, I usually end up learning fun things, too — like “F in the chat,” which apparently functions as a digital “pour one out for the dead homies” symbol that lets people pay their virtual respects to the fallen (according to Urban Dictionary).

Essentially, the chat gives viewers the option to share their reactions in real time the way they have no choice but to do in the actual theatre. For those who do choose to engage, the chat can capture digital equivalents of gasps, laughter, and tears in textual format.

Using the chat function has been especially interesting during performances of our production of Othello, given the play’s long performance history of disruptive audiences. Anecdotes abound about audience members attempting to prevent (or avenge) Desdemona’s murder somehow. Dr. Ayanna Thompson provides several examples in her introduction to the Arden Othello, like the one about the soldier at an 1822 production in Baltimore, who stood up in Act 5 and shot the actor playing Othello, breaking the actor’s arm.1 My personal favorite is the story about when famous Victorian actor Edmund Booth played Iago in an American frontier mining town:

The audience, which had not seen a play for years, was so much incensed at his apparent villainy that they pulled out their ‘shooters’ in the middle of the third act and began blazing away at the stage. Othello had the tip of his nose shot off at the first volley, and Mr Booth only escaped by rolling over and over up the stage and disappearing through a trap- door. A speech from the manager somewhat calmed the house; but even then Mr Booth thought it best to pass the night in the theatre, as a number of the most elevated spectators were making strenuous efforts to turn out and lynch ‘the infernal sneaking cuss,’ as they called him.2

True or not, the enduring existence of these anecdotes illustrates a history of tension between audiences and the play Othello that is very much alive today. As the Vimeo Chatbot, I can engage audiences in reflection or discussion about the troubling events of the play without pausing or in any way disrupting the action of the play itself. Sometimes that means dropping in “fun facts” to contextualize a particular moment or choice; other times, its means asking at-home audiences directly how they’re feeling about, say, bearing witness to Iago’s villainy in a way that forces them to confront any potential feelings of personal complicity.

In a time when we don’t get to hang out in the lobby or go to the bar after a show to talk through what we just saw, this chat function becomes increasingly valuable as an opportunity to engage people in a discussion about what they are seeing as they are seeing it.

Theatre is difficult to consume in a vacuum; the lessons are hard to learn (and easy to miss) if we are all receiving them alone, unable to share notes or compare experiences. The value of witnessing something as part of a collective, of talking to others within that collective about what you witnessed rather than taking our own individual assumptions for granted and for gospel, of learning not only from the thing we witnessed but also from the experience of witnessing it alongside others — these are the things we are desperately missing from live theatre that the digital distribution fix can’t supply.

Shakespeare is not going to think for us. His plays may “hold the mirror up to nature” (as Hamlet says a play should do) but a reflection is not the real thing. In order to tell the difference, you might need to engage in conversation and critical thinking about the topics at hand, expressing whatever emotions come up and taking in whatever feedback comes back from the others in the discussion in order to arrive at your conclusion. Conversation creates connection, and we all really need connection these days. Theatre may be a conversation-starter, but it cannot be the conversation itself. Theatre cannot connect us unless we talk about it together. As we continue to weather this pandemic, remember that the theatre is only as valuable as the conversations (and connections) it creates — and keep on finding ways to conversate.

Works Cited

- Shakespeare, William, et al. “Introduction.” Othello, Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare, 2016, pp. 41–43.

- Folger Shakespeare Library Scrapbook B.21.1. ‘Forrest, Edwin’ (quoted in Paul Menzer’s Anecdotal Shakespeare, pp 94-95).