Shakespeare was racist.

Well, probably.

Don’t get me wrong, I love the guy’s work. He was a brilliant playwright whose drama still speaks to the human condition. Plus we really can’t know that much for sure about him and his personal beliefs. But based on what we know of the Elizabethan England and the text, he was probably racist as heck by today’s standards. It’s really hard to get around that.

Titus presents issues of race that a modern audience cannot ignore. While the racial makeup of the 29 campers in session 1 is not 100% white, it is 90% white (which is, frankly, disappointing) and our diversity comes from our Asian-American and Latina campers, with nary a Black camper (African-American or otherwise) to be seen. As a result, the cast of our production is also 90% white. An all female, mostly white production (with the cast’s lone Asian-American teenage girl playing Aaron) is problematic at best, racist at worst, and dangerously offensive if done without careful thought and open dialogue. So… we have a problem. And while it’s a difficult one to talk about, we cannot and therefore will not ignore it. We have to talk about it, and be wildly uncomfortable doing so if that’s what it takes. A little discomfort in the face of an open dialogue about systemic racism within our whitewashed community is probably a good thing.

That being said: I’m a white girl. I spent many years of my life thinking the only thing I had to do to fight institutionalized racism was “not be racist.” Well, all it takes is a quick look at the state of this country to know that while there’s a lot of people “not being racist”, the problem is institutionalized racism is far from solved. That’s why camp admin has made it a priority to actively engage in this issue. Western culture has a long, dark history of racism, and I want to dive into it. However, I recognize this is going to be a seriously learning process for me and while I’m really looking forward to documenting that process on the blog, I recognize both that a) I have a lot to learn and b) I will very likely say some ignorant things on more than one occasion. . This post is the first in a series of race posts affectionately known as “Racism in Early Modern England i.e. Why White People (historically) Suck.”

Let the wokeness begin!

When we’re talking about race in Titus, we’re talking about Aaron, the one black character in the show (well, I mean other than his baby, but I want to mainly focus this investigation on Aaron). The play often refers to him as “Aaron the Moor” or simply “The Moor.” (The word “moor” is often used in Shakespeare to refer to people of color, but the word has a more complicated definition and history beyond this. I was actually totally unaware of this until Lia Wallace told me because I was so used to interpretation of Othello where Moor = Black and just never figured there was more explanation. But I’m going to make a whole other post about that!) Shakespeare portrays Aaron as the epitome of all evil. He advocates rape, cuts off Titus’ hand, devises the plot to have Martius and Quintus put to death, violently murders an innocent nurse (well, a racist nurse, but I think it’s safe to say that brutal murder was taking things a little too far), and does many other terrible things. And yet, by the end of the play he says the only things he regrets is that he “cannot do ten thousand more” (5.1.985). All because…he feels like it? Despite all the stuff he does, I don’t see any clear motivation for Aaron in the text. And any good actor knows that you can’t play a character (at least, you can’t play a character well) with no motivation. So why is Aaron the way that he is? In order to answer that question– well, I can’t. I don’t know why Shakespeare did what he did, and there’s probably no way for me to find out. But I can propose a theory! And my theory begins with a look at how race was viewed in Early Modern Europe.

Race was already a common idea in Elizabethan England, but racism itself was not even a word yet. While “the word ‘race’ entered the European vocabulary towards the end of the fifteenth century and became established as a scientific category in the nineteenth, the term ‘racism’ was not coined until the twentieth century.” (Wieviorka 66). There were black people in Elizabethan England, though many worked as servants or slaves. In fact, when King James said he wanted lions to pull his chariot through London, but lions were not accessible (oddly enough), he had two black men pull the chariot instead (Thompson). Black people were viewed as subhuman, and often stereotyped as being evil. In many Elizabethan works, “there seems to be a considerable confusion whether the Moor is a human being or a monster.” (Alexander, Wells 112). This is why Aaron would have been seen not as a fully developed person, but as a stock character that was no stranger to the Early Modern stage. Shakespeare’s audience would not have been like, “Hey, why is that guys so pointlessly evil?” They would have been like, “Classic Moor, am I right?” The association between evilness and blackness in the text is inescapable. Aaron even says, “Aaron will have his soul black like his face” (3.1.638) (Because apparently it’s particularly evil to speak in third person?) Clearly the people of Elizabethan England had some incredibly racist stereotypes about what a black character was supposed to be (unfortunately, not too far from stereotypes we still have today about black characters in the media). As history has proved time and again, people fear what they do not understand and what is different. It would have been easier for the audience to buy that the evil was coming from a black man, who they felt was “other” and “exotic,” than from the Roman characters, who were seen as more civilized. Afterall, Rome was considered the bastion of civilized society. It’s harder to question an idol than demonize something you were already taught to hate. So do we know for sure that Shakespeare intended Aaron to be evil solely because he was black? Nope. And we will never know. Still, Aaron fits pretty well into the Elizabethan archetype of “bestial moor”.

But as camp director Lia Wallace often reminds us, the text is a lie and nothing is real. Keeping in mind that “Shakespeare is super dead” is important. Even though there’s evidence Aaron was written to be purely evil due to his race, do we need to play him as such? It’s asking the wrong question to wonder how we are supposed to see Aaron. We should be analyzing how we, a contemporary audience, do see Aaron. I mean, he actually does say some pretty empowering stuff. Despite all scorn that’s directed at him, he is still owns his race and is proud of it.

For instance, when the nurse laments that Tamora’s child was born black, a clear marker that Aaron, not Saturninus, is the father, she refers to the child as “a devil” (4.2.819) and calls the situation a “joyless, dismal, black and sorrowful issue”, thus equating all of those adjectives with the idea of blackness by its very nature. Now Aaron gets a lot of sick burns in this play (yes, we all know I am talking about “Villain, I have done thy mother” (4.2.829). “What a thing it is to be an ass” (4.2.800) comes in a close second.) but his response to this is one of my favorite lines: “Zounds ye whore, is black so base a hue?” (4.2.824). He is fully aware of the implications his skin color has in this society, but he nevertheless embraces it. Wait, what? Shakespeare? Old white man? Wrote this? That’s…oddly progressive of him. Then again, Aaron has been portrayed as pointlessly evil this whole time. Are we supposed to believe him or disagree with him? Is this supposed to be thought provoking or just more evilness? The answer is simple: It doesn’t matter. Because (say it with me now) Shakespeare is super dead. Again to quote Lia, “Shakespeare is not going to come back from the grave and go ‘That’s not what I meant!’” (though to be fair, my first thought if that happened would not be like, “Shakespeare I’m so sorry I interpreted your play incorrectly!” it would be like “Whoa hey look it’s Shakespeare. What’s he doing here? Isn’t he super dead?”)

With all this in mind, the fact that we are faced with the “The Titus Thing” is no surprise. We have a black character and no black campers to play him. Keep in mind Aaron would originally have been played by a white man in black face. Early modern theater was racist from the very beginning, so it makes sense that Shakespeare is not a huge draw for people of color today. But does it have to stay that way?

This gets at the question of reclaiming. We know that as a society, we do not now accept what Shakespeare’s audience accepted. So is performing the play now enabling those beliefs or empowering the people they hurt? Considering the fact that we are in fact doing the show, I am inclined to say the latter. However, as a white girl, I don’t think I’m really qualified to answer that question. Some productions of Titus have portrayed Aaron as more empowering. In Greg Doran’s 1995 production, the whole play took place in South Africa. Titus was an Africaans general and the weakening of his family represented that failure of the apartheid. Aaron was not simply an evil doer, but a revolutionary fighting against colonisation and oppression. Doran wrote that it made Aaron “emerge as a much more complex and intriguing character” (“The Horrifying Fascination”). However, I wanted to get a sense of how we could approach all this in our production, so I went to our very own Aaron, Sam Chu, for some input.

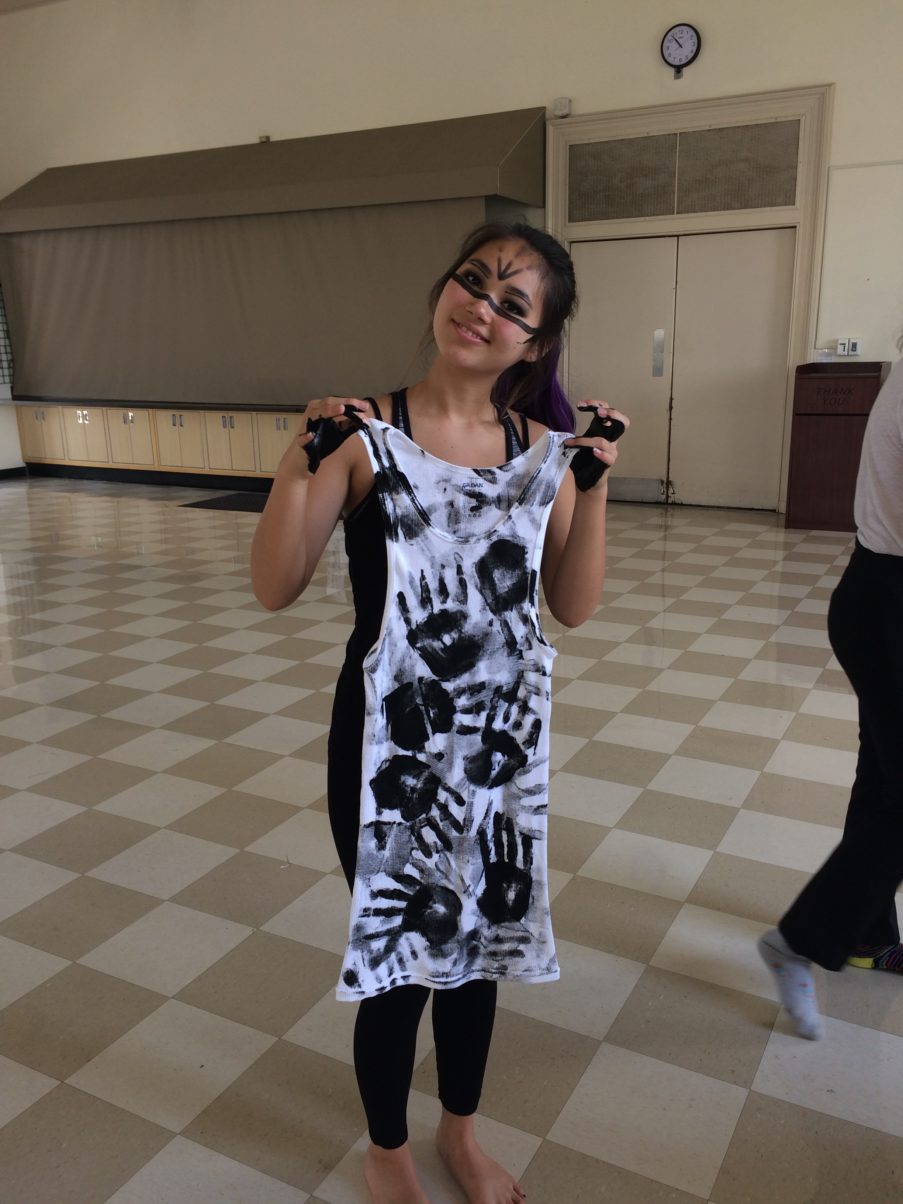

Sam has been doing an excellent job working on the role of Aaron. Since I’ve been playing Chiron, I get to work with her a lot and it’s been really wonderful. It’s hard to miss, though, that Sam is one of the only non-white campers, cast as the only specifically non-white character. Sam is half Chinese. She actually doesn’t mind being cast as Aaron. She says, “I think in a camp that’s 99% white people…if you had some diversity and you didn’t utilize it, it would have been kind of weird.” In fact, she’s no stranger to being confronted with racial issues on the stage before. She was once cast as Jasmine in a nearly all white production of Aladdin. Sam described the experience of meeting the cast for the first time and realizing that a play that takes place in Iraq would be performed by almost exclusively white people. “It was really weird” she recalls.

As far as playing Aaron, Sam has noticed the unfair way he is treated in the script. “I honestly think he’s been kind of villainized…probably because of his race…Because he is black, he’s supposed to be the main character who’s evil and no one’s supposed to care about him that much. He just kind of does what he does and is what he is….He’s meant the be the dark, the black, the villain, and just because he is black, everyone hates him. Just like racism now. And in Shakespeare’s time.”

Nevertheless, she has been finding some humanity in him, “Sometimes he’s just flat out evil. I think he’s evil with a little bit of a heart.” In fact, in some ways she relates to his experiences with discrimination. She says that while she culturally identifies as more white, she still owns her ethnicity.“I still feel a sense of pride in my Asian side…I do take pride in that I am more than just caucasian.” She imagines that much of the racism directed at her as a child went over her head, but still recounts how her school experience was somewhat segregated. Most of the Asian students hung out together, and being half-Asian, she only felt half in with that crowd. “There was this joke in math class…I am not good at math…and people would say ‘dumb Asian’ and I would be like, ‘huh, that’s really weird, because I thought that just because I was Asian I was smart’…it’s kind of like the expectation to be who you are…I thought that was kind of weird and rude.” Though of course the experiences of Asian Americans and black Americans are not the same, it seems pretty undeniable that anyone who is not white faces some kind of discrimination in this country, even if it comes out in the form of microaggressions. Sam is not the same race as Aaron, but she still finds the way he deals with his treatment somewhat inspiring. “He doesn’t take it to heart. Like I never took it to heart…He knows they say it, but he’s strong enough and he knows who he is…he is whoever he wants to be. I kind of respect him in that way.”

While she seems to be enjoying the role, Sam does think that there are many things the ASC could do to increase diversity. “I know that a lot of the kids from here are from specifically acting schools or schools for the arts which normally cost more…A way to do that is maybe to reach out to different places…sometimes people of color feel ‘wrong’ in theater place because it’s mostly been just white people…If you reach out to schools that don’t necessarily have the opportunity or money, that would be good…I have some friends in Hampton, Virginia… in a normally black neighborhood…and they don’t even know what ASC is.”

No doubt the problem of diversity in the arts, specifically Shakespeare, is something we as the ASC should be working to bolster. These are certainly not issues we should ignore. In the meantime, I am hoping we can make a production of Titus that is still sensitive and relevant. As Sam noted, Aaron can still serve as a symbol of racial pride, and that can be relevant to all people who face racial discrimination. I think the best passage to end on is one that Sam noted as one of her favorites as it showcases Aaron’s strength. When protecting his child, he proclaims, “Coal-black is better than another hue,/ In that it scorns to bear another hue./ For all the water in the Ocean,/ Can never turn the swan’s black legs white” (4.2.843-6) Despite everything, Aaron won’t yield to the racism he faces. “He takes pride in his race and knows that he will never be white” Sam says, “He can be who he is and be proud of it. Yeah. I like that.”

On a slightly lighter note, here’s a really fantastic Key and Peele sketch about race in Shakespeare. Warning: There is a fair bit of profanity.

Works Cited:

Alexander, Catherine, M. S. and Wells, Stanley. Shakespeare and Race. Cambridge Universety press. 2000

Chu, Samantha. Personal Interview. 25 June 2017.

“The Horrifying Fascination of Titus Andronicus.” Times Higher Education, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/culture/the-horrifying-fascination-of-titus-andronicus/2004241.article#survey-answer

“Shakespeare’s Racism in Titus Andronicus” Dirty Hand Sam. https://dirtyhandsam.wordpress.com/2014/05/08/shakespeares-racism-in-titus-andronicus/

Thompson, Ayanna. “Shakespeare and Race”. Video. Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/category/arts-and-humanities/literature/shakespeare/race/?cc=us&lang=en&

Wieviorka, Michel, The Arena of Racism. SAGE Publications. London: 1995