With schools and universities closing their doors and students and teachers opening their laptops, I’m seeing and hearing lots of trepidation about making the leap to online instruction. The American Shakespeare Center has worked for years to facilitate student learning through our workshops, study guides and supplementary materials. Today, I want to give those of you about to make the leap to online instruction some specific ways to use these materials with your students while you are away from them. We love collaboration and play and the ideas below will continue to lean on those as a means of learning. When you and your students reunite, you will be able to continue far ahead of where you were when you parted. Below, I will take you through a suggested use of the ASC Materials for online teaching practice.

ASC Study Guides

ASC Study Guides

ASC’s collection of 20 titles you can download, each with 20+ activities and keys, you can immediately deploy a complete Shakespeare unit with your students. Beginning with the basics, your students will use ASC rehearsal room techniques to explore the text and begin to think like an actor. Each activity helps them to “go fishing” for staging and performance clues that they can then play with in a collaborative way in scheduled online sessions.

Assessment

For assessment purposes, I recommend a “commonplace book.” Lots of examples of commonplace books survive from Shakespeare’s time and provide great portraits of “active reading.” Your students can create their own memoirs of study, both written and visual, in a number of different ways–with google education suite, a website, a pinterest page, a blog. For more on the history of commonplace books and some examples of assignments that accompany them, visit https://sites.google.com/site/literaryelements/1/commonplace or https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/the-commonplace-book-assignment/.

Pre-Reading Activities

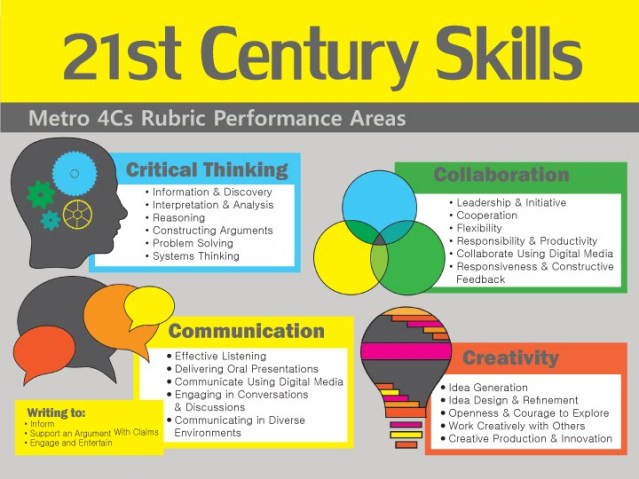

After establishing the commonplace book, begin your study of the play of your choice by exploring the Shakespeare Timeline–ask your students to note possible influences on Shakespeare’s plays that arise from the events of his life and record their observations and anything that inspires them.  Then consider Shakespeare’s Stage Conditions–the world in which he and his fellow actors worked– in order to connect these texts to the act of playing, remember: they are more like blueprints for performance than novels or poetry. Check out the Stuff That Happens as a primer for the story–remembering that Shakespeare’s audiences were familiar with the plots of the plays they went to see, and that what matters is less what happens than how Shakespeare tells the story. Since this section doesn’t go all the way through the play ask them to predict what happens next for each character in the introduction, in their commonplace book. Finally, check out the Who’s Who, descriptions of characters delivered in quotes from the play. Throughout the unit we want the students taking what they find in Shakespeare’s words and making their own choices based on what they see–thus, we don’t say “Hermia is Egeus’s mistreated daughter–in love with Lysander but sought after by Demetrius” because we want them to see the possibilities for Hermia in the words of the play– this is at the heart of the approach. And influences each section of the guide. We are offering ways for students to create the characters they find by teaching them the tools actors use–tools (by the way) that are useful in so many areas and are deeply connected to the principles of teaching 21st Century Learners. They will be thinking critically in order to create high quality work, and communicating their ideas as collaborators.

Then consider Shakespeare’s Stage Conditions–the world in which he and his fellow actors worked– in order to connect these texts to the act of playing, remember: they are more like blueprints for performance than novels or poetry. Check out the Stuff That Happens as a primer for the story–remembering that Shakespeare’s audiences were familiar with the plots of the plays they went to see, and that what matters is less what happens than how Shakespeare tells the story. Since this section doesn’t go all the way through the play ask them to predict what happens next for each character in the introduction, in their commonplace book. Finally, check out the Who’s Who, descriptions of characters delivered in quotes from the play. Throughout the unit we want the students taking what they find in Shakespeare’s words and making their own choices based on what they see–thus, we don’t say “Hermia is Egeus’s mistreated daughter–in love with Lysander but sought after by Demetrius” because we want them to see the possibilities for Hermia in the words of the play– this is at the heart of the approach. And influences each section of the guide. We are offering ways for students to create the characters they find by teaching them the tools actors use–tools (by the way) that are useful in so many areas and are deeply connected to the principles of teaching 21st Century Learners. They will be thinking critically in order to create high quality work, and communicating their ideas as collaborators.

The Basics

- 100 lines

We recommend working through the first 100 lines of the play together, then assigning to each student their 25-100 lines that they will explore and teach to their peers. We start diving into the play with a series of activities that encourage students to pick up on the nuances that reveal places where actors can make a choice for playing. So, it is good to experience how those choices can play out.

- Choices

In an online meeting with your students, or having them film themselves, use the first line of the play to work through the Vocal section, then move on to the Physical section and have them use the lines provided. They can respond to the impressions left by the activity in their commonplace book.

- Embedded Stage Directions

Start by studying the image of Blackfriars Stage on Page 10. Discuss the entrances, the audience arrangement, the gallery above, the trap below. Point out the center entrance’s size compared to the doors flanking it, and explore why it might be called a discovery space. Look at the gallant stools and think about what it means to have audience members onstage. Now, consider the text. Read through it in a round robin–each student reads to the first end stop–a period, question mark, exclamation point, or semi-colon. Note the varying lengths of phrases, and which character speaks most, which least. Using the ASC Basics book mark (see graphic, left), go through the possible ways that Shakespeare directs with the text.

Read through the lines once more and look for any of the available options–mark them using the symbols provided. Using your teacher’s guide and the stage image, pose questions to your students about the possible movement in the scene–remember there will be many correct responses!

- Paraphrase

Moving onto another activity for close reading, show your students the image of the first 100 lines (they will be making one of their own for their lines). Discuss (or have them respond to the prompts) what is the hardest word? (if it is a name, you can point out that there are still “hard” names; the point of the exercise is that they know almost every word–Shakespeare’s words are not hard, but his arrangement of them might be). Note the different sizes of words, ask what the importance of the largest words on the page may be. Ignoring prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions, and proper nouns, ask them to word for word paraphrase two or three lines using a dictionary or thesaurus–but leave the order of the words intact. What they may find is that Shakespeare chose the simplest word. They will also find that some characters speak in funny ways, just like some humans.

- Verse and Prose

Now it is time to get into the nitty gritty, important distinction of verse from prose and the implications both have for playing. Once students have a handle on this, they will be able to find many ways to explore choices for the various characters they come across. We like to think of meter as the language of the heart, while prose relates to wit–or head. Using your section on this facet of Shakespeare’s plays, explore how to begin to see the character come to life.

- Rhetoric

Round out your close reading activities with a consideration of the arrangement of the words and what that can tell you about a character. Using the scoring system ASC has developed, find the patterns in your first 100 lines and mark them so that the tendencies of characters and moments become clear. Then discuss the implications. What are the choices an actors could make based on the continual repetition? What could be behind a character substituting one word for another? Where are their overlaps? Does the character seem to be intentional about the word arrangement, or is it due to a disturbance?

- Asides and Audience Contact

When we think about Shakespeare’s theatres, the final element to consider (and ultimately, one of the most important elements) is the audience. Because Shakespeare and his fellow actors performed is spaces in which they could see and interact with the audience, the scenes and plays function as conversations between more than just the characters onstage. In this section, your students take over for the editors and choose where an aside is possible and why an actor might choose one.

- Classroom Exploration

In this section, which offers different activities for each play, you will find things like Textual Variants, Perspectives (an interdisciplinary approach often offering primary sources and other historical information and then connecting the subject under examination to today), staging challenges, deep dives into rhetoric or meter, even activities looking at leadership, marriage, women, blood on stage, cue scripts, and much more. Many ways into the plays with deeply detailed readings and activities examining moments in the play at hand.

- Production Choices

The final section of the guides offers, perhaps, the most opportunity for creative expression and collaboration. In it, your students could work together to cut a scene or the play using google docs or another cooperative tool. They will learn about costume, how to double, how to schedule time for rehearsal–perhaps you might assign two or three to “stage a scene” with the Blackfriars playhouse image and drawing tools.

Other resources

- ASC has an array of hour long productions drawn from our camp festivals. These accessible performances show how the stage works and allow your students to see other students successfully wrestling with challenging texts. Consider showing a scene or a full production so you can discuss cutting text, costume choices, interpretations, and more. See a sample of our Hamlet, Q1 below (and go to the ASC Theatre Camp YouTube channel for more).

- As an alternative to assigning blocks of text, you might have each student examine a character using a cue script. We are the benefactors of a wonderful tool using Folger Digital Texts that will pull a cue script for any character in the cannon–students could use the techniques above to develop a methodology and understanding of the world of the play from one point of view, just as Shakespeare’s actors would have done.

- ASC can also visit your classes through a virtual workshop or tour. Our workshops will illuminate the text in active and fun ways, while our tour might be a good way for your students to envision themselves on the stage as they think about the plays.

For any of these resources, please email me at sarah.enloe@americanshakespearecenter.com.

We face some challenges in the coming days. I am hopeful that we can help, and look forward to hearing from you.